While exploring options around School Based Health Centers (SBHCs), there are key areas which ought to be considered. Excellent SBHC resources may be accessed for free from the national School Based Health Alliance website. From exploration of the research literature, as well as conversations with affiliates of RSA, the topic at the forefront of many stakeholders’ minds is financing – especially considering the startup costs to begin an SBHC. Other important factors to consider in starting up an SBHC are discussed below. While this list is not comprehensive, it does serve as a good start.

1. Identifying Funding Opportunities:

A primary concern for school districts is that around startup costs affiliated with beginning centers. One major space for SBHCs to gain financial support is to engage with federally-based grants. According to the literature, partnering with a committed grantmaking agency may provide an opportunity for supporting these costs. In rural regions, one key opportunity is through the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy’s Office for Advancement of Telehealth. These were first made operational in the 2017-2018 school year (Love et al. 2019a). Additionally, strong SBHCs may attain long-term financial sustainability when existing in states with enhanced Medicaid reimbursement rates. This could look like Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act, as well as the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Furthermore, State Title V Block Grants and other similar federal initiatives have played a key role in ensuring SBHC success (Fowler et al, 2018). Yet, while federal plans for SBHCs may vary by administration – it is important to consider the role of state-provided funding through policy (Sprigg et al., 2017). Notably, over the past two decades, the rates of SBHC expansion proved to be nearly double for those 16 US states which offer SBHC funding (65% cumulative increase in SBHCs), relative to states which do not offer state government funding for the centers (26% cumulative growth in SBHCs) (Love et al., 2019). New York State does offer support for SBHC funding and thus ought to be explored for state-level grades as well. The best place to start is with NY State Grants Gateway– a suggestion made to RSA by Sarah Murphy, the Executor Director of the New York State School Based Health Alliance. One piece of advice offered by the New York State School Based Health Alliance is to connect with other schools and districts which are working off of funds, and ask them about the grants they are searching for – as a way to gain advice and a roadmap for where to start.

In order to remain sustainable, a strong partnership between a school’s SBHC and its sponsor is crucial to ensure success. Here are links to resources for exploring partnerships:

-

NYS School-Based Health Center Sponsor Directory (with Dental)

-

School-Based Health Centers: A Funder’s View of Effective Grant Making

2. Developing Core Competencies

The School Based Health Alliance offers seven core competencies in which all SBHCs ought to show proficiency in order to ensure effectiveness. (These topics will be discussed in the next post.) It has been noted that in forming partnerships between schools and healthcare providers, that schools should allow the medical staff at an SBHC to focus on their work. With that said, it is specifically important, one SBHC leader noted, to identify a “Point-Person” on the school or district-side who is exclusively dedicated to work on SBHC partnership.

3. Internalize Principles and Guidelines for School based health Centers in New York State.

If you’ve determined that you’d like to open a SBHC, it is of particular importance to note that in New York State, policy mandates that “All SBHCs must provide age appropriate, on-site, core primary care services that comply, in content and frequency, with New York State’s Child/Teen Health Plan (CTHP). Age appropriate reproductive health care is to be considered an essential component of comprehensive primary care”. According to Dr. Chris Kjolhede of Bassett Healthcare and SBHCs: “Talking about reproductive healthcare with adolescents is, is just as important as talking about vaping, smoking, alcohol abuse, weight management, good exercise activities, all of that.” Furthermore, 24-hour coverage and requisite collaboration with a sponsoring healthcare agency is necessary (Sipple and Casto, 2007)

While the Principles and Guidelines for School Based Health Centers in New York State lays out all areas, here are a few to focus on:

Consider SBHC Space and Site Requirements – It is also necessary to follow guidelines and have sufficient space for SBHCs within a school, as per Principles and Guidelines for School Based Health Centers in New York State. For example, “Space must be adequate to accommodate the multi-disciplinary staff, and to afford the client verbal/physical privacy, and to allow for ease in performing necessary clinical, clerical and laboratory activities.” For more specific details on the size, equipment, and other required resources, Section G: Facility Requirements.

Consider the Role of The Community– According to Section C: Relationships of the Principles and Guidelines for School Based Health Centers in New York State.”The SBHC recognizes that it functions within the community and should draw upon and contribute to its resources.” It is important to consider the SBHC’s role as a player embedded into the community.

Consider Evaluation Plan – In Section H. Quality Management and Improvement, the Principles and Guidelines for School Based Health Centers in New York State stipulates that “There should be written, specific, quality management policies and procedures, which include staff and program evaluation.” While this is oftentimes an area that is underdeveloped in SBHC work and research, Evaluation Plans are necessary in order to ensure ongoing improvement and to collect important data for ongoing refunding of grants (Brindis et al., 2016). Ultimately, the School Health Services National Quality Initiative (NQI), led by the School-Based Health Alliance and the National Center for School Mental Health and funded by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, has established a set of SBHC standardized performance measures that align with national child quality measurement initiatives and definitions. It would be prudent to engage these measures – to report on performance measures annually and use their data in improving and building awareness of centers (Love et al, 2019).

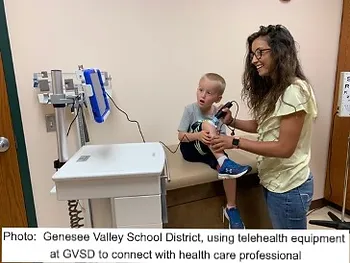

The next post will explore the creative approach which one district, Genesee Valley, took in order to provide school-based health to its students: Blog Post 5: Promising Advances in rural SBHCs, and Genesee Valley School District’s work with Telehealth.

References

Brindis, C. D. (2016). The “State of the State” of School-Based Health Centers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(1), 139–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.03.004

Fowler, T., Matthews, G., Black, C., Crosby Kowal, H., Vodicka, P., & Edgerton, E. (2018). Evaluation of a Comprehensive Oral|

Health Services Program in School-Based Health Centers. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(7), 998–1007.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2478-1

Love (a), H., Panchal, N., Schlitt, J., Behr, C., & Soleimanpour, S. (2019). The Use of Telehealth in School-Based Health Centers.

Global Pediatric Health, 6, 2333794X1988419. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X19884194

Love (b), H. E., Schlitt, J., Soleimanpour, S., Panchal, N., & Behr, C. (2019). Twenty Years Of School-Based Health Care Growth

And Expansion. Health Affairs, 38(5), 755–764. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05472

Sprigg, S. M., Wolgin, F., Chubinski, J., & Keller, K. (2017). School-Based Health Centers: A Funder’s View Of Effective Grant

Making. Health Affairs, 36(4), 768–772. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1234